Egypt has always been known for its abundant reserves of gold, and ancient miners made sure to thoroughly exploit all economically viable sources using traditional methods. Apart from the resources found in the Eastern Desert, Egypt also had access to the riches of Nubia, as seen in its ancient name, nbw, which is the Egyptian word for gold. The hieroglyph representing gold—a wide collar—was introduced in Dynasty 1 when writing first began, but the earliest gold artifacts that have been found date back to the preliterate era of the fourth millennium B.C. These artifacts mainly consist of beads and other small items used for personal decoration. Gold jewelry, whether intended for daily wear or for use in temple or funerary ceremonies, continued to be crafted throughout Egypt’s extensive history.

In Ancient Egypt, the gold they used often had silver mixed in, and it seems like they didn’t bother refining it to make it more pure. The color of the metal was different depending on how much silver was in it. From a bright yellow boss on an old vessel to a paler grayish yellow uraeus pendant from the Middle Kingdom, the variations in hue were all because of the natural presence of silver.

The pendant actually has a combination of gold and silver in almost equal proportions, making it electrum. This natural alloy of gold with over 20% silver was described by the Roman scholar Pliny the Elder in his work Naturalis historia.

During the Amarna Period, an Egyptian goldsmith took a unique approach by mixing copper with a natural gold-silver alloy to create a ring featuring Shu and Tefnut, giving it a distinctive reddish tint.

The preservation of gold artifacts is heavily influenced by mishaps throughout history and during excavation processes. In Egypt, for example, sites have been pilfered for centuries and a significant amount of precious metal has been melted down over time. As a result, there are not many surviving gold pieces from the Early Dynastic and Old Kingdom eras. The Metropolitan Museum, for instance, only has a small bangle bracelet from the tomb of Khasekhemwy, the final ruler of Dynasty 2, as representation from that period. This bracelet was crafted from a wide strip of hammered gold sheet. Additionally, small stone vessels that had been sealed with hammered gold sheets designed to look like animal skin, and secured with gold wire “string,” were also unearthed in the royal tomb.

Malleability, which is most noticeable in gold, is the ability to be flattened into thin sheets. This property is why many ancient Egyptian gold artifacts, like a ram’s-head amulet from the Kushite Period, have survived in solid, cast form. Although small and rare, these objects showcase the remarkable malleability of gold.

Even in ancient times, people were able to create gold leaf as thin as one micron. They would use thicker foils or sheets to give various materials a golden surface, like the wood of Hapiankhtifi’s ancient collar or the bronze mount of a basalt heart scarab from the New Kingdom.

The leaf was attached to the collar using gesso and linen, while a thicker foil was squeezed between the bronze mount and the scarab for added detail. Gold inlays were commonly utilized to improve various artworks, particularly bronze statues.

In ancient times, Egyptians loved wearing gilded glass jewelry, especially during the Ptolemaic and Roman eras. The technique of gilding silver likely originated in the Near East, possibly in Iran. While its use in Egypt during the late first millennium B.C. is still not fully understood, during the Roman Period, a new method of gilding with mercury, borrowed from East Asia, became widely used for silver and copper-based jewelry in the Mediterranean region. This technique continued to be popular well into modern times.

Archaeologists digging at Dahshur, Lahun, and Hawara in the early 1900s discovered a treasure trove of jewelry once worn by high-ranking women connected to the royal courts of the powerful Dynasty 12 rulers Senwosret II and Amenemhat III. One standout piece is Sithathoryunet’s stunning pectoral, crafted using the intricate cloisonné inlay technique. This involved placing countless hammered gold strips, known as cloisons, in partitions on a gold back plate made from various hammered sheets and cast elements. The back plate’s reverse was also intricately designed with matching patterns and additional decorations. While the pectoral was undoubtedly prized for its beauty and skillful construction, its main purpose was ritualistic: inscribed with Senwosret II’s name, it symbolized Sithathoryunet’s dedication to ensuring his eternal well-being.

Despite the control of gold as a trade item being mainly in the hands of the king, Egyptians who were not of royal status still possessed gold jewelry. Amulets from the Middle Kingdom era often showcase granulation, a technique that involves using small metal spheres to add intricate details and raised patterns, like zigzags. These granules were typically attached using colloidal hard soldering, a method that involves a chemical reduction process with finely ground copper-mineral powder to lower the melting point of the gold surfaces. This results in a physical bond through the diffusion of gold and copper atoms between the granules and the hammered sheet, creating a strong connection.

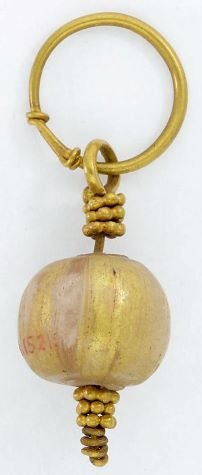

Another crucial technique used for bonding precious metals in both ancient times and the present day is soldering. This process involves creating an alloy, known as solder, with a lower melting point than the metals it is meant to join. The solder is shaped into small squares or strips, called paillons, which are strategically placed and heated to melt. This localized melting helps reduce the melting point of nearby gold surfaces, allowing for the molecules to diffuse and bond between the solder and the components being joined. Evidence of early soldering techniques can be seen on a Dynasty 12 gold ball-bead necklace found on the mummy of Wah, while more intricate work can be observed on the electrum uraeus pendant.

The incredible amount of gold discovered in Tutankhamun’s tomb, the only ancient Egyptian royal burial found mostly intact, showcases unimaginable wealth. Egyptologists believe that kings who lived to a ripe old age were likely buried with even more luxurious goods in preparation for the afterlife. Additionally, lesser-known members of royal families during the New Kingdom were also buried with extravagant gold treasures.

Three foreign women who were believed to be minor wives of Thutmose III were buried together, each with a collection of gold jewelry and funerary items. Among their treasures were matching pairs of gold sandals, intricately decorated, as well as cosmetic containers crafted from a variety of materials and adorned with gold detailing.

Historical records tell us about the abundance of statues made of gold, silver, bronze, and other metals that were used in Egyptian temple ceremonies. However, only one gold statue has been found to still exist. This statue depicts Amun, with its body crafted in one piece but missing its arms, which were attached separately. The figure holds a scimitar in the right hand and an ankh symbol in the left, with the ankh made up of multiple parts soldered together. Some experts believe that the missing crown, attachment loop, and support of the statue were intentionally removed before it was acquired for the Carnarvon Collection in 1917, rather than being a result of ancient damage or burial.

Utilizing wire technology is vital in the realm of goldworking, especially in the creation of jewelry. Wire was commonly used to add intricate designs to pieces, often paired with granulation work, and secured in place using the colloidal hard soldering technique. These wires could be manipulated in various ways – twisted, braided, or woven – to form chains and also played a structural role in connecting different elements of a piece together. The wires themselves were crafted from tightly twisted metal strips or rods, or from square rods that were shaped into round form through hammering. The strap chain fragment, consisting of yards of wire, was made using the former technique, while the wires on the electrum uraeus pendant were shaped through hammering.

During ancient times in Macedonia, Ptolemaic, and Roman periods, jewelry from different regions circulated in Egypt, influencing local production. A new trend in jewelry design in Egypt during the Roman era was incorporating gold coins, a departure from the commodity-based economy in earlier times. This technique, known as opus interassile, involved piercing settings to frame the coins, showcasing a fusion of Roman and Egyptian styles.